Engineered Catalyst Design and Forming

ChemCatBio 2026 Technology Brief

ChemCatBio hosted a webinar highlighting the design, composition, and production of engineered catalysts, which are critical for moving transformative bioenergy technologies from the laboratory out into the commercial sector.

Bridging the gap between laboratory- and engineering-scale catalysts requires more than just an understanding of scale. It means transitioning high-performance research powder catalysts into physical forms that are suitable for operation in commercial-scale reactors. That constitutes both a step change in the complexity of the formulation and a departure from traditional laboratory-scale processing methods.

Elements of the Engineered Catalyst

Composition Is Critical, but the Engineered Catalyst Must Consider More

How ChemCatBio Uses and Makes Catalysts

Perspectives on Engineered Catalyst Design and Forming

ChemCatBio Webinar, 2023

Elements of the Engineered Catalyst

An engineered catalyst is a multicomponent catalyst formulation that includes the necessary additives to achieve the performance and physical requirements for operation in a commercial reactor. This compares to a laboratory catalyst, which is composed of a single bulk phase or an active phase on a support. Engineered catalysts possess the mechanical strength for larger-scale operation and have the necessary chemical stability to achieve lifetimes that enable an economically viable commercial process.

Engineered catalysts incorporate a variety of important physical, chemical, and mechanical components.

How ChemCatBio Uses and Makes Catalysts

The increased complexity of engineered catalysts, compared to their analogues used at earlier stages in research, can result in unforeseen performance consequences if great care is not taken during the translation step. ChemCatBio uses a systematic development approach to address such concerns toward the first generation of engineered catalysts for commercial applications.

Five Steps To De-Risk Catalyst Design

- Identify Catalyst Targets: What are the components of the catalysts that must be faithfully reproduced in the engineered form? What performance targets have been outlined by process modeling that the final catalyst must achieve?

- Identify Physicochemical Requirements: Based on the target reactor type and configuration, what are the engineering constraints (e.g., acceptable pressure drop, attrition resistance, mechanical strength, cost)?

- Invite Industry Input and Review: When practicing catalyst forming at small laboratory scales, shortcuts or methods may be wholly incompatible with industrial-scale unit operations (either intentionally or unintentionally). It is important to ground early-stage efforts with industrial know-how on catalyst scale-up, such that learnings at one stage translate to the next.

- Select Forming Unit Operations: Determine appropriate equipment and manufacturing methods based on industrial input, the engineering constraints of the process, and the targeted form.

- Assess Best Practices: While some hold catalyst forming as a “dark art,” there is a great deal of institutional knowledge on this type of processing that researchers should assess before venturing to prepare a first-generation engineered catalyst.

Derisking Conversion Technologies That Use Engineered Catalysts

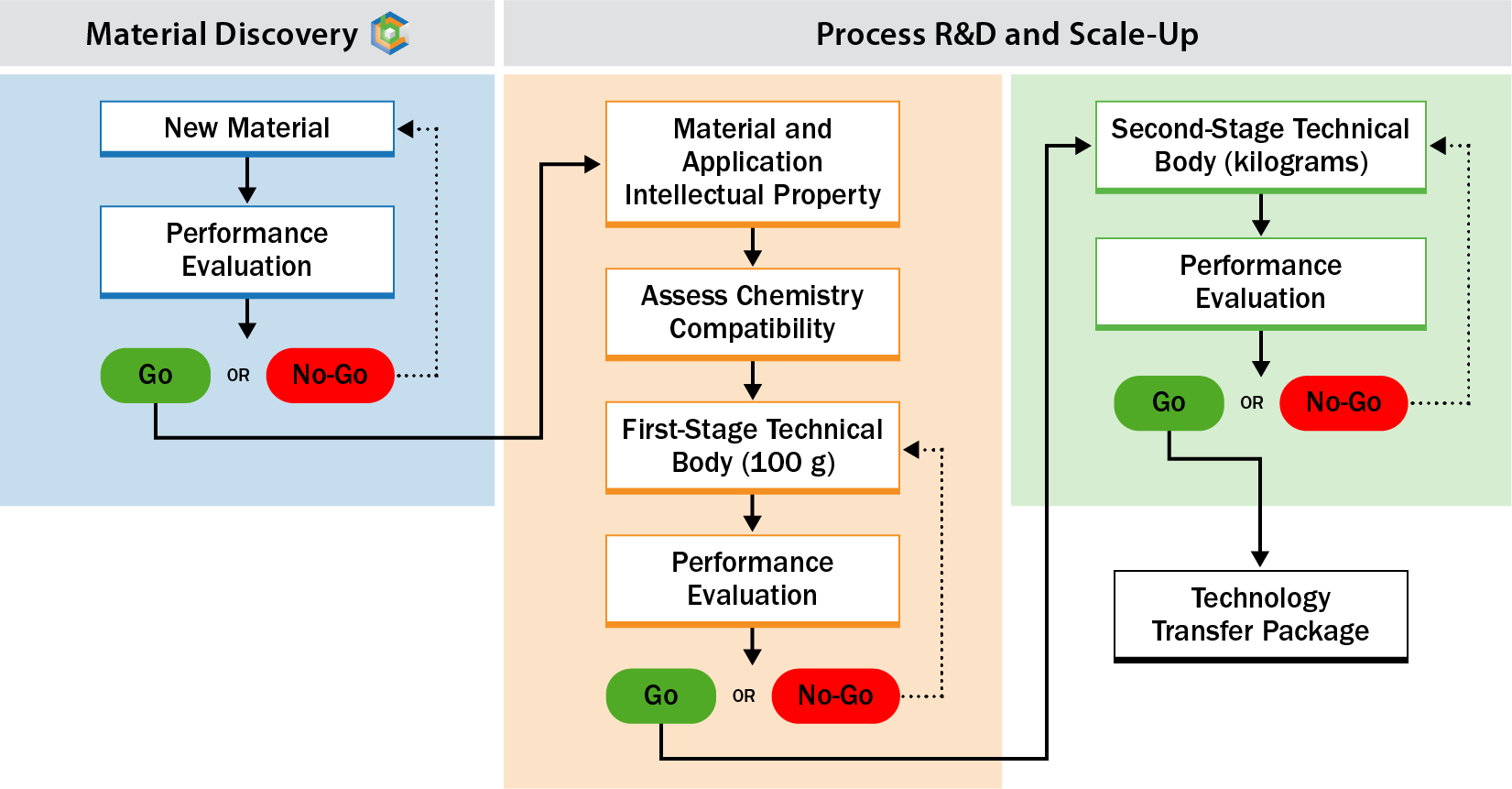

ChemCatBio uses a stage-gate approach to identify research powders suitable for translation into engineered catalysts. On an application-by-application basis, ChemCatBio projects set stage-gate criteria (i.e., materials cost, lifetime, conversion/selectivity) for materials and processes, which must be met before work begins to develop first-generation engineered catalysts.

ChemCatBio's stage-gate approach to materials discovery, scale-up, and manufacture.